Video game physics are something that we often take for granted. If you make your avatar jump, you expect it to come down and not go shooting off into space. Although, if you have played Skyrim long enough, you know that this can happen anyway. However, aside from glitches, quirks, or intentional game physics that don't mimic the real world, we expect in-game objects to behave in ways that make sense, so we don't think about that fact that these laws must be baked into the game.

Programming physics into a game can be as simple as one or two routines with a few lines of code each, or as complex as requiring a completely separate physics engine like Havok or PhysX with millions of lines of code. Regardless of the complexity or whether a game engine requires middleware to handle the computations, game physics falls into two broad categories --- rigid body and soft body.

Rigid body physics is generally defined as forces that act on a solid object. It is required for most 2D and 3D games. Soft body physics is applying physical forces to a deformable mass --- like a flag. Soft body is much more complex to simulate. For this reason, it is used far less and depending on the game, may not be required at all.

In this article, we'll delve a bit deeper into these two types of physics and explore how and why they are used in video games. We will avoid the deep technical dive for now, but may investigate the complexities further in a future installment.

The Importance of Game Physics

Developers apply physics in games for a variety of reasons, but the most important factors to consider are intuitiveness and fun factor. If an object in a game does not behave in a predictable way, it would be tough for the player to figure out how to play.

For example, if you started a FIFA 20 match and whenever the ball hit the turf it bounced in a random direction, it would be very hard, if not impossible to figure out how to get it down the field and into the goal. Therefore, game makers try to simulate how the ball will bounce based on trajectory, velocity, and other real-world factors, so that the player intuitively knows how to manipulate the ball or any other object. Ironically, FIFA 20 has suffered a spate of bad user reviews precisely because its physics don't work as fans expected.

However, that is not to say games have to abide strictly to the natural laws of physics. In fact, most developers bend the rules for the sake of fun. The game has to be enjoyable to play after all. If the physical forces are too lifelike, it can ruin the fun factor. For example, imagine what it would be like to play Grand Theft Auto V with unforgiving physics --- there's a mod for that by the way.

Even a slight collision with another object at high speed would result in a wreck ruining the player's getaway. Not so fun.

So there is a fine line between making a game enjoyable to play and it being physically realistic. It is the responsibility of the developers to strike the proper balance, which is often dependent on the demographic they are targeting. Racers are a good example.

Many gamers enjoy arcade-style racers, like Need For Speed, that don't punish them too harshly for scraping a guardrail or taking a corner too fast. A smaller demographic prefer sim-racing games that are a closer approximation to reality, such as Gran Turismo. Even when creating sims to satisfy a smaller market, game makers have to find a way to lure other players, or else the game will do too poorly. Gran Turismo initially relied on photorealism to attract other players, which worked to an extent. Still, Polyphony Digital eventually added an arcade mode to the series to cater to a broader market.

Now that we know why game designers employ physics, let's take a closer look at the two types, how they are used, and what developers do to keep the calculations required from exceeding processing capabilities.

Rigid Body Physics

When we think of video game physics, we are usually considering rigid body physics (RBP) as this is arguably the most important, and something that most games must implement in one way or another. Rigid body physics deals with simulating and animating physical laws on solid masses. For example, the ball in the FIFA 20 case above is a rigid body that is acted on by the game physics.

Whether it is a 2D game like Pong or a 3D such as Skyrim, most video games deal with linear rigid body physics.

2D Video Game Physics

Let's go all the way back to Pong --- two rigid bodies (ball and paddle) repeatedly colliding with each other. Gee, when you put it that way, it doesn't sound fun at all. The granddaddy of video games did not realistically model real-world physics. For one, its programmers ignored calculations involving gravity, friction, and inertia. It was just a ball going back and forth at a constant speed.

Second, the angle of the ball rebounding from the paddles was not calculated accurately. The ball's bounce completely ignored the law of reflection. This law states that disregarding other factors such as spin, a ball striking a surface at a given angle will rebound at an equal angle.

In Pong, the reflection angle was determined by the proximity of the impact to the center of the paddle. Regardless of its initial trajectory, the ball's reflection was based on how far from center it struck the paddle. So players could completely reverse the ball's momentum, regardless of its incoming vector.

Angular trajectory would come into play more with later iterations and other paddle games like Breakout. However, even then, the numbers were usually fudged. It all comes back to the fun factor. Mimicking deflection too closely to reality was less fun and often more difficult to play.

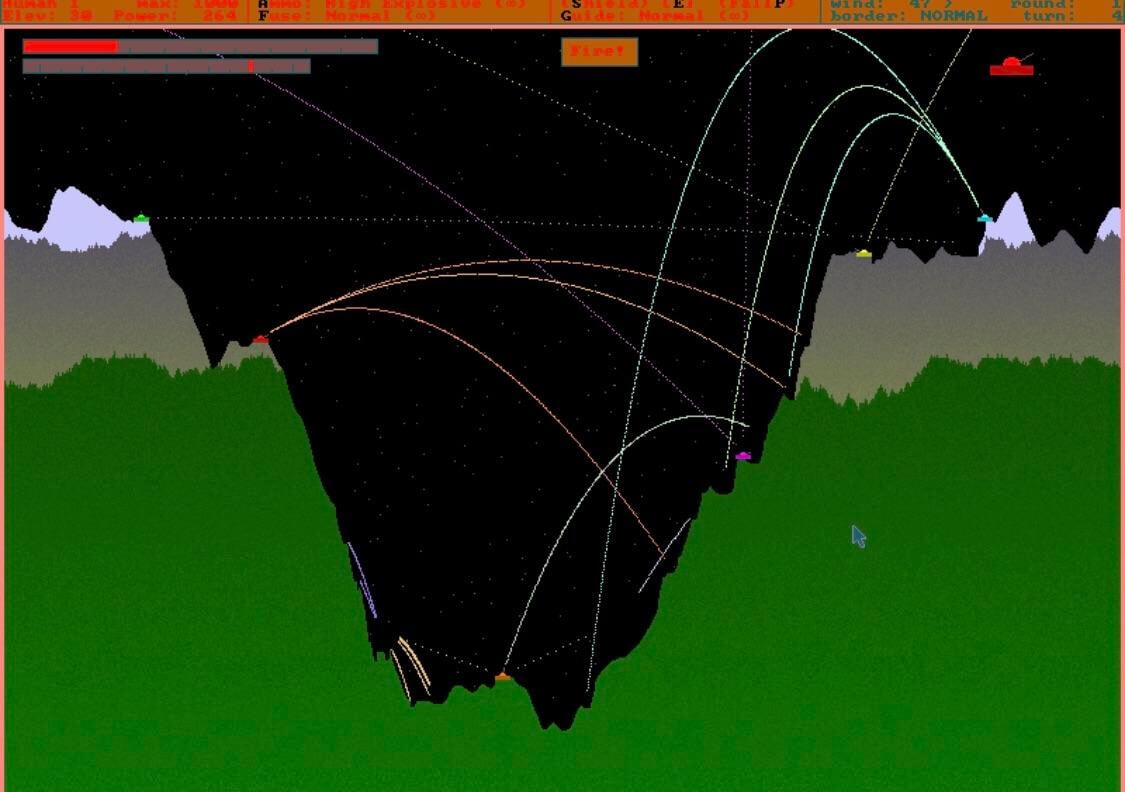

Artillery games were the first to start incorporating factors like gravity and resistance into the mechanics. For those too young to remember, artillery games were where players would take turns firing cannonballs, arrows, or other projectiles at each other trying to destroy their opponent's base. These games used semi-realistic ballistics that took account for things like the angle of launch, gravity, wind resistance, and initial velocity. Again, designers did not make the games too true-to-life. Their target audience was the average joe, not ballistics experts.

The rigid bodies in artillery games, primarily the projectiles, were acted upon by the various forces, and the animations adjusted accordingly. Arrows or missiles are a good example of animating a rigid body in these games. While the plane of the projectile would change during flight, the arrow itself would remain straight. It did not bend as it completed its arc, which is what we would expect. This example might seem oversimplified because of its intuitiveness, but it is important to understand when distinguishing it from soft body dynamics. Any two points on an object in a rigid body system will always remain the same distance apart.

Games like Donkey Kong, and subsequently the Mario Bros games, set the stage for how physics would affect the 3D games to come.

Our good plumber Mario complied with very general physical laws like gravity, momentum, and inertia, even in the earliest games. Jumping was the primary game mechanic, and it has since become a staple that will never go away. When dealing with jumping and gravity, we intuitively know that what goes up, must come down.

The question is, how high does it go up, and how fast does it come down? It is something developers have to consider carefully in their game design; just how close to reality does the game's gravity have to be?

If Mario was forced to obey real-world laws, he would probably never make it past level one. So, developers had to find that balance to make the game playable while maintaining the intuitive expectations players would have about how Mario should behave in his world. Later games would stretch the bounds further by introducing the double jump. Super Mario 64 was the first game in the series to implement the double jump, although it was used in prior games, as far back as Dragon Buster in 1984.

The double jump allowed players to leap higher vertical or horizontal distances to clear gaps or reach ledges. The game mechanic became popular in platformers almost to the point of overuse. It is still a staple in many modern platforming games but is also seen in 3D games like Devil May Cry and Unreal Tournament as well, which brings us to the 3D realm.

3D Video Game Physics

The physics used in 3D games is not that much different than what developers used in their 2D cousins. As mentioned before, even the double jump exists in some 3D games. The main difference is the complexity of the computations when adding in a third dimension (z-axis) and objects made up of multiple rigid bodies.

In most 2D games, developers only have to contend with detecting the collision of a few solid objects at a time. For example, Mario landing on top of a Koopa. Any part of Mario can touch any part of the Koopa. How that contact occurs determines whether the Koopa gets bopped or Mario loses a life. Either way, it is only one collision.

Most 3D titles have multiple solid objects interacting with each other. Take the Uncharted series as an example. When Drake scales a cliffside, the program is looking for collisions with at least his hands and feet, which are all separate rigid bodies. If he leaps and only one hand catches a ledge, the animation will be different than if both connect.

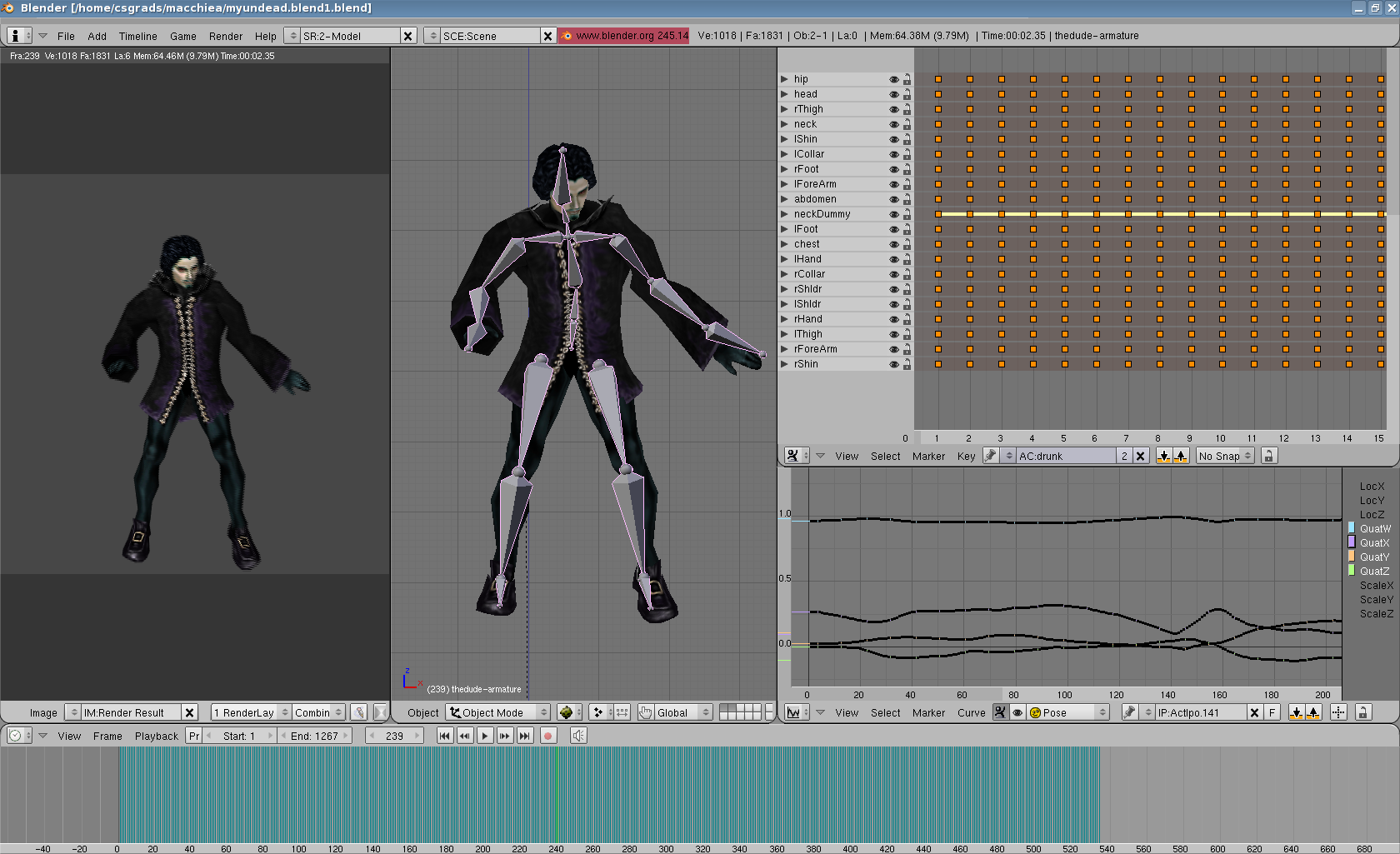

Speaking of each limb being a separate rigid body, 3D games (and some 2D) have models with multiple rigid bodies held together at joints. In other words, a human model's arm may have a hand and a forearm connected at the wrist with that linked to an upper arm and so on. This structure and how it behaves is referred to as "ragdoll physics."

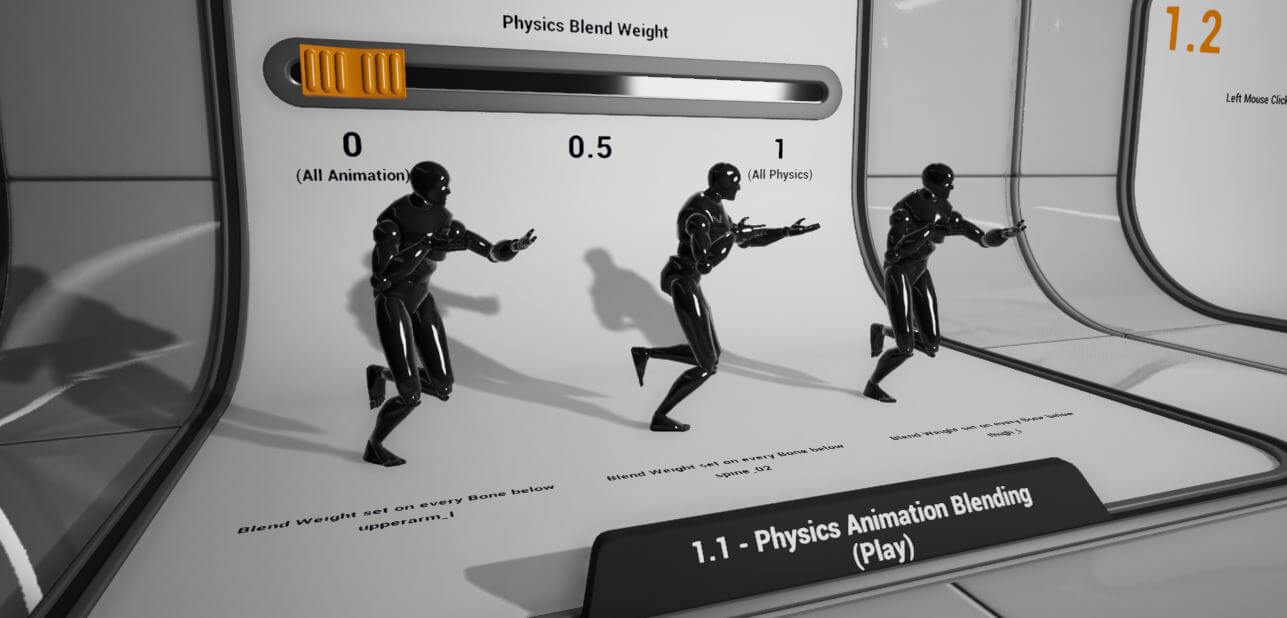

Ragdoll physics is used in most, if not all, games with player or NPC models. The connections of the various rigid bodies that make up the limbs are created on the game engine's skeletal animation system. Each rigid body must act under a set of rules to look realistic when moving.

To compute these movements, programmers use a variety of techniques. The most common is Featherstone's algorithm, which is a constrained-rigid-body approach that keeps the limbs from flying around like airplane props, although sometimes they still do to comedic effect.

Other types of ragdoll handling approaches include Verlet integration (Hitman: Codename 47), inverse kinematics (Halo: Combat Evolved and Half-Life), blended ragdoll (Uncharted: Drakes Fortune and many others), and procedural animation (Medal of Honor series).

All of these techniques attempt to solve the problem of a body going limp too fast and crumpling to the ground with its joints going this way and that like --- well, a ragdoll. The rigid bodies making up a model are constrained in their movement so that they behave in a predictable manner, even if the the game's physics are not completely based in reality.

Just as in 2D titles, game makers have to find a balance between realism and fun. So when computing physical forces within the game, the calculations are often not entirely accurate; that is to say, "the game cheats."

Take the Sniper Elite series as an example. In the real world, military snipers have to make every shot count, so they consider quite a few factors when lining up a target. Wind speed, wind direction, range, target movement, mirage, light source, temperature, barometric pressure, and the Coriolis effect are just a handful of variables that real-life crack shots have to factor into their position and aiming.

If Rebellion chose to go the route of making an authentic sniping simulation, not only would the game be very difficult for most players, the number of calculations, and thus the amount of programming and processing power would increase significantly. Crunching these variables is not taxing on today's processors, but the average player does not want calculate these factors when playing, let alone even understand them. Therefore, it is much simpler (and profitable) to just allow the player to line up the target in the crosshairs and let them score a hit, preferably with a slo-mo bullet cam.

That is not to say that games have not attempted to make sniping more complicated. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare has a campaign level that involves taking out a target from long range. The player must contend with the Coriolis effect and wind speed/direction (above). The mission is frustratingly tricky, enough so that I eventually put it down and played something else. That is not to say that some players do not like that challenge. Some called it the best mission in the game. I just don't have the patience for it.

Racers are another genre where a lot of calculations are done regarding rigid bodies and the forces applied to them. Tire meets the road, chassis connects to the wheels, cars bumping one another, and many other solid objects have to be calculated into collisions actively and passively.

Physical forces pushing the cars during cornering are usually fudged, especially in arcade racers, making drifting extremely easy when compared to real-life but still challenging enough to give players a sense of accomplishment when they pull off a tricky maneuver.

The forces acting on cars in sim racers like Gran Turismo or Assetto Corsa are more realistic and take into account several factors that arcade racers ignore. Assetto Corsa Competizione (version 1.0.7), for example, introduced a five-point tire model into the game.

This five-point physics model consists of two contact points on the front edge of the tire footprint, two on the rear, and one in the middle. Most other racers just have a single point of contact on each tire. Each of the regions acts as a connected rigid body. They can move and flex in three dimensions, independently reacting to forces and surface contact. This sophisticated model allows for much more realistic reactions when cars, for example, strike or edge up on a curb.

However, the extra contact points up the calculations done by the physics engine considerably. Fortunately, ACC's engineers have figured out a way to do this without increasing the computational load so much as to affect game performance negatively.

As you can probably tell, physics models in 3D games can be far more complicated than their 2D counterparts. Many more variables and collisions must be tracked to keep the physics on an even keel. However, most calculations are still linear and, therefore, more straightforward than soft body physics models.

Soft Body Physics

Soft body physics (SBP) deals with deformable objects and is far more complex than RBP, which is why we saved it for last. It's also less utilized and more simplified in video games than its rigid body counterpart because of the massive amount of computation it requires to simulate realistically. Therefore, all soft-body models in video games are brought down to a manageable level in one way or the other due to processing limitations.

Some soft body physics examples would be cloth, hair, and collections of particles like smoke or mist. Unlike a rigid body where any two points remain the same distance from one another, soft bodies can morph and move so that two points on the body can move closer or further from each other.

Soft Body Solids

There can be many restrictions on the amount of movement in a soft body, or there can be none. For instance, let's look at a flag. All points on the flag are constrained to remaining on that flag --- they can't just go flying off into space. However, as the flag moves, the distance between any two points can vary. The range that they can move away or toward each other depends on the distance between them when the flag is flat.

In other words, adjacent points are constrained to remain adjacent, while distant ones can move close enough to become adjacent but cannot become more distant than their flat state span. The number of configurations of all the points on the flag, while finite, is still staggering.

The calculations required to simulate a billowing flag using an SBP model accurately far exceeds the capabilities of single processor CPUs and GPUs. So, developers often rely on shortcuts to mimic the random movement of a flag blowing in the wind. A manual looping animation is one straightforward method but can look canned after a while, so it is best used where the flag is not the center of attention.

Clothing, while nearly identical to a flag in its soft body properties, is more challenging to apply physics to, both because it is a focal point for the player and because it often is more dynamic in terms of player input. Batman's cape in the Arkham games is a perfect example.

Designers cannot use looping animations for Batman's cape because its morphing relies on how the player moves. It cannot just flap around randomly like a flag because it will not look right. If the player moves to the left, the cape has to move to the right to realistically simulate the forces of inertia and air resistance acted upon it.

To handle these complex variables, game makers employ physics engines to handle the work for them. In Batman: Arkham Knight, developer Rocksteady used APEX Cloth PhysX. This tool allows designers to create a mask for cloth bodies and set parameters for how it should move. Depending on how it is configured, anything from silk to burlap can be simulated.

The parameter settings also allow programmers to limit the natural forces on the fabric for the sake of better performance. For instance, "Wind Method" can be set to "Accurate" or "Legacy." Legacy ignores drag and lift, thus reducing the calculations that need to be done.

Additionally, not all points on a piece of cloth are factors. Instead, portions are grouped together, reducing the number of vertices that need to be accounted for from millions to tens of thousands. Even then, not all of these groupings interact with one another as they would in an actual soft body system. Mainly they only interact with nearby points, which brings the number of mathematical computations done to a very manageable level.

Soft Body Particle Systems

Unlike fabric or hair, particles such as smoke or clouds are far more complicated to simulate. Any two points within a particulate object can move in a nonlinear fashion. They are not constrained to the confines of the soft body, meaning one or more points can move beyond what can be considered the limits of the object and can even form other soft bodies.

You don't have to look that far back to find games where explosions, fire, smoke, or dust looked unrealistic because manual animations were used. Even some contemporary titles put very little focus on particle physics because it is too difficult and taxing on the processor.

However, physics engines have improved particle systems to a great degree over the years. Just watch the title screen of Skyrim to see how realistic illusions of smoke have become (below).

Generally speaking, each particle in a soft body system has a static lifespan. This period goes from the time it is spawned to the time it fades away before being respawned from the particle's source. During that time, the point will move according to set parameters.

Take smoke from a campfire, as an example. Each particle is animated with a trajectory that is generally up and away from the source (the fire). The particles do not travel straight up in a linear fashion, but rather swirl and randomly change their position in 3D space. They do this until they are removed from the simulation, based on their lifespan.

The lifespan roughly determines how realistic the particle system looks. A long lifespan tends to create very realistic campfire smoke but is taxing on the processors. A short lifespan is more forgiving computationally but results in particles that only go up a little way from the fire before disappearing.

Going back to the Skyrim title screen example, the smoke effect here looks very realistic because there is nothing else happening on the screen other than menu selection, which takes minimal CPU cycles. So the full power of the CPU and GPU can be devoted to simulating smoke particles with very long lifespans. As you watch you can see the particles evaporate before they are respawned again.

Switching to actual gameplay, you will notice that smoke around fires is not as realistic looking. It is still pretty convincing, but watching it for a while will reveal that it relies on shortcuts to replicate a particle system. Developers can do this in a number of ways, including shortening the amount of time a particle remains in the simulation, but they may use other tricks as well. Interlacing a number of static smoke layers is a common method.

In short, soft body physics in all games is limited. For one, it is not necessary to fully simulate SBP since it is usually just there for aesthetics. Secondly, accurately replicating a soft body system requires too much horsepower making it impractical to implement on gaming systems. Full SBP simulations are best left in the physics labs.

What Have We Learned

Video game physics is a complex field where developers must find a balance between realism and the compromises set by computational limitations. Finding shortcuts and relying on physics engines allows programmers to mimic real-world physics quickly and efficiently so that they can focus on more critical aspects of the game like the mechanics.

The bottom line is to make it fun. Realism takes a backseat to engaging gameplay. This is not to say that game physics is optional. On the contrary, designers must employ it in one form or another, or else the game will be chaotic with no intuitive rules. They can also bend the natural laws to make gameplay more fun and rewarding, such as including the ability to double jump.

If you are interested in the more technical points of video game physics and the way that game makers employ physics engines, there are several resources to get your started. Check out the physics section in the Unity manual or the Lumberyard tutorials. We may also cover the topic in more depth in a future article.

In the meantime, it may be fun to think about the things we have discussed as you play your next video game. Just like we explained how 3D rendering works in video games, can you spot shortcuts developers have used or find innovative ways that they employed physics in a manner that enhances gameplay? Give it a go and let us know.